Ten things I like and don't like, including this MVP race

One last round of 10 things before All-Star Weekend:

What a visceral thrill watching the insane shot-making of George and Harden intersect last Saturday in Houston.

No matter how many think pieces we write, I'm not sure we can adequately appreciate in real time the revolutionary nature of Harden's step-back 3. Harden has canned 173 step-back triples, per Second Spectrum; Luka Doncic remains second ... with 53. Absurd.

Harden is on pace for almost 270 step-back 3s. Stephen Curry led the league with 272 3s as recently as 2012-13.

Harden is now pulling this craziness in the corners:

It is hard just staying in bounds there under pressure. Harden is somehow executing lunges.

Curry pioneered the step-back to clown big men on switches. He fakes toward the hoop, gets them backpedaling, and moonwalks into a triple. Curry needs the space that initial fake opens. He is shorter than Harden, and brings the ball lower on his windup. Harden requires minimal prelude.

No opponent has any idea what to do with this. Coaches from two teams told me they instructed defenders to stand still and raise their arms when Harden steps back instead of leaping at him -- risking a foul. If that's the best answer, the league is in trouble. I seriously think the solution might be having Harden's defender just run at him, screaming and waving his arms -- that or the extreme strategy Milwaukee used in mounting Harden's left shoulder.

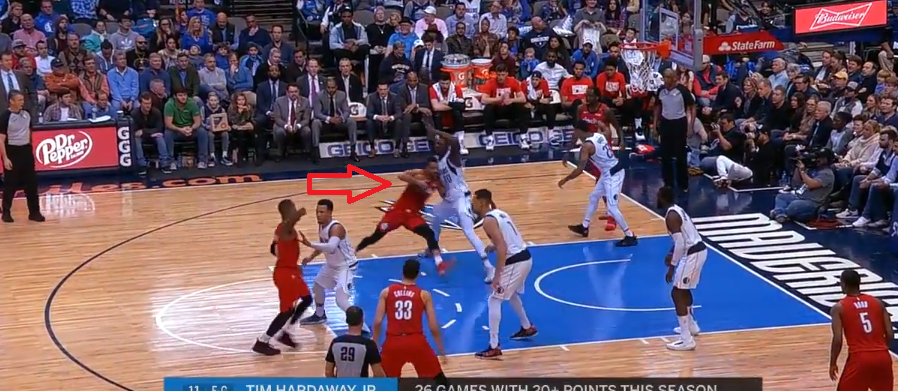

Step-back mania has almost obscured that Harden continues to hit ridiculous 3s out of the pick-and-roll. You watch this and wonder why Dennis Schroder lingers on Harden -- leaving other Rockets open -- after George has recovered from Iman Shumpert's screen:

Then this happens few minutes later and you realize, oh, that's right, Harden can fire from 30 feet if given a sliver of daylight:

We have perhaps overlooked George amping up his shot-making derring-do. He has drained 23 step-back 3s, fifth overall, and since he often has a height advantage, he needs zero space:

George has hit a preposterous 50 percent of tightly contested 3s, easily the best mark among 77 rotation players who dare try at least 0.5 such shots per game.

He'll launch out of the pick-and-roll even if his guy remains on his hip -- literally touching him:

George is averaging 29-8-4 on a 45/41/84 shooting line, and he might be the favorite for Defensive Player of the Year. The Thunder are plus-11 points per 100 possessions with George on the floor, and minus-11 when he sits -- the largest such positive differential (about plus-22) of any player, and it is no longer close, per NBA.com. They collapse without George, even when Russell Westbrook remains in the game.

For those who value defense, we officially have a three-man MVP race betweenGiannis Antetokounmpo, Harden and George -- with Joel Embiid lurking close behind, followed by the Golden State stars, Nikola Jokicand Damian Lillard.

Legal experts on all sides concede they have never seen anything like this -- a player so good demanding a trade so publicly, with so much time left on his contract. When the trade deadline passed, the Pelicans wanted to sit Anthony Davis. The league said no. The Pelicans feared the maximum $100,000-per-game fine, though the league denies explicitly threatening it.

Even rival GMs sympathetic to the Pelicans acknowledge complexities. The league has a responsibility to paying fans and broadcast partners. The players' union might fight any mandated rest for Davis, arguing it would amount to retaliation -- not health preservation, or something else traditionally at a team's discretion.

They did not mount such a fight on behalf of JR Smith, presumably riding a PhunkeeDuck somewhere, because Smith acquiesced to his banishment. The Chandler Parsons and Enes Kanter situations from this season are not quite equivalent, either. The Grizzlies claimed they needed to see Parsons in G League action before trusting his knees. The Knicks might have argued Kanter was not a meaningful upgrade over their younger centers.

Awful teams shifting minutes to young players is common practice. The league is fine with bad teams buying out veterans -- serving as midseason farm systems for contenders. They do nothing when teams sit players on the trade block for a game or two -- not two months, mind you -- around the deadline. To the league, the Davis situation is different.

Davis would play basketball in some form -- risking injury -- even if the Pelicans rested him. In theory, playing him also keeps open the possibility of New Orleans going on a run, and Davis changing his mind. (In real life, that ship has sailed.)

Those screaming that Davis ruined the Pelicans are forgetting that the Pelicans participated in their own ruination by failing to build a good enough team around him.

And yet: The NBA's warning feels draconian. Davis upend the Pelicans. He and his people requested a trade, and iced the market so New Orleans had only one option: the Lakers. New Orleans should have some recompense.

The league seems to be tacitly acknowledging that by allowing New Orleans to limit Davis's back-to-back appearances and perhaps his minutes, per Adrian Wojnarowski. If the league tacitly acknowledges the Pelicans have a point, well, then, don't they have a point -- and shouldn't they be able to handle the situation as they'd like?

The league is aiming at a compromise. That is understandable. But case-by-case compromise results in inconsistent enforcement. The league did nothing during the Kanter drama because no one other than Kanter and some vociferous New York fans cared -- and because it had a predictable end date. People care about Davis, so the league did something. What it did is too harsh. New Orleans should get more leeway.

This is a thing, again:

LeBron gives the ball up and watches, statuesque, even though he has Boban freaking Marjanovic on him. This is Chill Mode Offense.

LeBron can do this on 20 possessions and still notch triple-doubles. A lot of his workload metrics -- speed and distance covered, drives, pick-and-roll volume, free throws -- are consistent with the past few seasons. He is recovering from his first extended injury absence.

He has reached an age where he needs to conserve energy. He ceded large chunks of the offense against Indiana in last season's first round until Game 7. Perhaps this is the price of getting full-throttle LeBron when it matters.

But his shots in the restricted area are down, and he's taking more super-long 3s. He is posting up about 2.9 times per 100 possessions, half his typical rate, per Second Spectrum. He was a more engaged off-ball player in Miami and during the early years of his second Cleveland stint. He did not retreat so often toward half court, blowing on his hands, as possessions wound away.

It has been hard for the Lakers to develop a stylistic identity with LeBron toggling between passivity and chess-master control. Close your eyes and picture a Lakers half-court set. What do you see?

Bystander LeBron has contributed to the vibe that he exists outside the current roster. (The public Davis drama amplified that vibe.) It also brings out the worst in Brandon Ingram. You almost see Ingram and the other Lakers look around before they all agree LeBron is out of the play, and that they must proceed accordingly. If Ingram has the ball and no one sets a prompt screen, he might laze into a fadeaway jumper.

LeBron's previous teams could afford heavy doses of dialed-back Bron. They played in the East. The Lakers play in the West.

It has become axiomatic that Aaron Gordon is not a wing, and that Orlando continuing to play him as one alongside both Isaac and Nikola Vucevic is stubborn folly. Against top defenses, that is probably true, and might remain so for years.

But this trio has been sneakily solid despite the Magic employing zero starting-caliber point guards to guide them. Orlando has outscored opponents by almost six points per 100 possessions with their ultra-big frontline, per NBA.com.

We know what Orlando wants defensively -- length, length, length -- and Isaac is going to be a multi-positional destroyer. They will rise and fall on the other end. The idea is that Gordon and Vucevic bring enough shooting and playmaking to open the floor. The execution is uneven, but you see flashes -- including the occasional use of Isaac as rim-runner:

Terrence Ross is on the floor there in Gordon's place. That matters. Gordon is shooting just 34 percent from deep. Defenses stray from him to bump cutters. But unlocking this part of Isaac's game is important. It hasn't been easy; Vucevic is Orlando's primary screener, and Gordon needs reps, too.

The Magic won't pry huge openings with all three on the floor; everyone has to get comfortable slicing through tight corridors. Isaac has been better over the past month attacking scrambled defenses off the catch:

He is averaging 14.5 points per game in February, the best scoring month of his career.

Isaac has hit just 29 percent from deep; until he proves a threat from there, smart defenders will just wait for him in the paint. But he's trying more 3s, and his stroke looks smoother.

I'm officially intrigued with what these guys might do if Orlando found a real point guard. Old-school size can work if it comes in a package of new-school skill. The Magic held onto Vucevic, signaling they are open to re-signing him. I'm in for Gordon-Isaac-Vucevic until Mohamed Bamba is ready.

Speaking of classic size and modern skill: Sacramento has something with the Bagley-Giles pairing. After struggling early, the Kings have played opponents close to even since Jan. 1 with these two on the floor -- a huge victory considering a lot of those minutes come with De'Aaron Fox and Buddy Buckets on the bench.

There will be clunky nights. They can over-clutter the paint. Bagley usually defends power forwards, and like most teenaged bigs, he has trouble calculating whether to help or stay home:

But holy hell, are these guys skilled. They outrun plodders in transition. Both can beast in the post, a handy thing, since one often has a size advantage over the opposing power forward. Giles has a graceful lefty hook:

Giles is an ace passer from the elbows. They have enough smarts between them to slip interior passes through tight spaces.

Bagley is startlingly explosive. He springs off the ground twice in the time it takes most bigs to jump and land once. He's comfortable facing up, and straight-up mean shoulder-checking dudes on baseline drives:

He will shoot more 3s eventually.

On defense, they both have potential to protect the rim switch across multiple positions -- the holy grail.

It's early. They have a long way to go before they can thrive together against opposing starters, or defend lineups loaded with shooting. With Harrison Barnes on board, Dave Joerger has the luxury of bringing the duo along slowly.

He has done well juggling combinations without overtaxing any of them. He has played Barnes at both forward spots, including at power forward with Bagley at center.

Barnes played most of the past three seasons at power forward. In most alignments, that is the right place for him. But he shoots well enough to slide down, and the Bagley-Giles duo may not end up looking like "most alignments."

If Willie Cauley-Stein's free agency gets too pricey, the Kings should be comfortable letting Cauley-Stein walk and signing a minimum-ish placeholder. Giles and Bagley have shown enough.

McCollum's 3-point shooting has normalized after an icy start; he's shooting 40 percent from deep since Jan. 1.

McCollum's midrange artistry never abandoned him. He's shooting an even 50 percent on midrangers, and he has perhaps the league's deepest bag of floaters, runners and trick shots.

A personal favorite: when McCollum cuffs the ball like a running back burrowing through the line before reclining, knees up and foot extended to clear space, into an unblockable leaner.

A lot of guards use funky grips to navigate thickets, but you rarely see such extreme football-style cuffs. McCollum tucks that sucker under his armpit!

McCollum palm the ball. He started cuffing it in elementary school, before he could palm it, and the habit took. "It's just more comfortable for me in traffic when there could be contact," he says.

The Blazers need to get consistent minutes out of folks beyond Damian Lillard, McCollum, Jusuf Nurkicand Jake Layman (LAYMANIA! is sweeping the nation!), but they are a tough out as long as Lillard and McCollum are clicking.

Lyles is shooting a career-worst 25.4 percent from deep, and he's getting too thirsty trying to force his way out of a slump:

Lyles can't be jacking like this off the bounce early in the shot clock. Denver's bench units -- great all season -- can do better.

At points, Lyles has been an important ingredient in those lineups. When he doesn't suffer tunnel vision, he's a smart ball-mover. He has a mean-spirited post game against mismatches.

But he's shooting too often. Every pairing of Nikola Jokic and Denver rotation regulars has a positive scoring margin save one: Jokic and Lyles. That probably isn't a coincidence. (The much-derided Jokic-Mason Plumlee look is killing it, by the way. Another point for Mike Malone!)

I'd like to see more of the Lyles-Paul Millsap pairing when Jokic rests, but between injuries and Lyles' shaky jumper, Malone hasn't gotten to it much. Lyles logged just 14 minutes combined in Denver's past two games, and he's in danger of falling to the fringes of the rotation as the Nuggets get healthy.

I would have paid good money to be a fly on the wall in Atlanta, when Quin Snyder -- then a Hawks assistant -- and Kyle Korver watched film together to conceive increasingly complex methods of springing Korver. That is some "Beautiful Mind"-level whiteboard tinkering -- on the border between genius and insanity.

But Snyder might want to bag his recent experiment using Rudy Gobert as a pick-and-roll ball handler on scripted out-of-bounds plays:

I get letting the defense-first big guy eat, but there is such a thing as being too creative. Gobert is a star because he sticks to what he does well.

Good player development coaches keep it simple: work on the stuff you do in games, and break those skills down into mini-skills. Case in point: Allen's improved passing in the pick-and-roll.

There are several passes available to big men in full flight. The Nets have worked on each, one by one. This is not a complex pass, but Allen makes it with speed, confidence and calm accuracy. He knows where everyone is, or at least where they should be, before he catches the ball.

There are lots of steps left: mastering every pass; learning tendencies of both opposing teams and individual defenders; and total enlightenment -- manipulating the defense instead of reacting to it. But Allen is doing well in the early stages. He's dishing two dimes per 36 minutes, up from 1.2 last season, and looks more in command.

It's not original, but no player has busted out the "call me!' hand gesture with the frequency and glee of Dedmon after made 3s. This is a happy byproduct of behemoths venturing outside: They are so excited to try this forbidden fruit, they develop ritualistic celebrations.

It doesn't matter if Dedmon is sprinting back on defense to quash a fast break; he will take a half-second to flash the "call me!" sign. (Important: I checked with Dedmon via the Hawks, and the intended meaning is that he is "dialed in from deep," per a team spokesman.)

I love everything about this: Dedmon's all-in commitment, the specificity of the gesture's meaning, and the fact that his hand resembles an ancient flip phone. Jeff Van Gundy would be proud.

Also: Dedmon is getting pretty damned good! He has hit 38 percent from deep on a career-high 155 tries. Dedmon had attempted one triple before last season.