Those experiencing 'Ozempic shaming' speak out about the backlash they faced

The drug used to treat diabetes surged in popularity last year as many turned to it to lose weight.

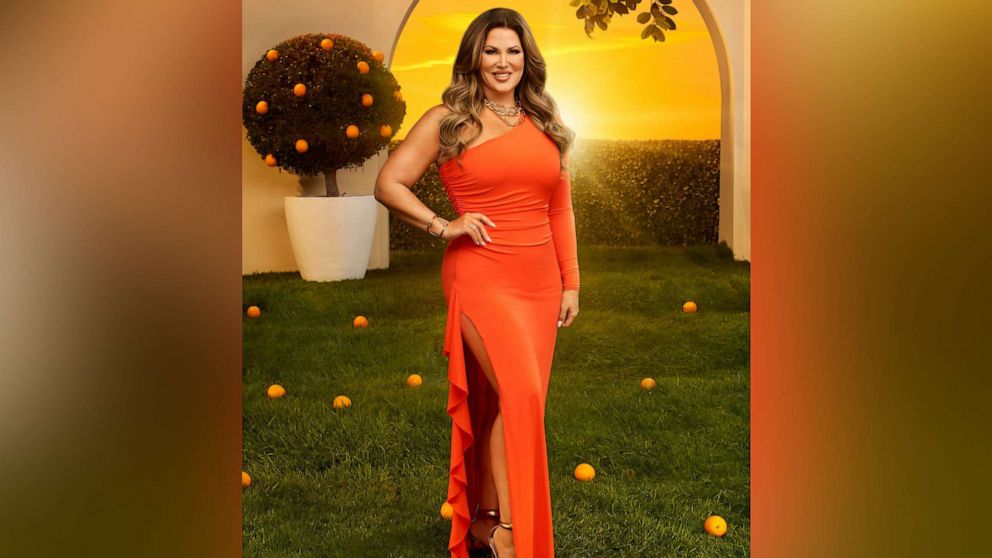

When the reality TV show "The Real Housewives of Orange County" finished filming its latest season last November, star Emily Simpson said she found herself depressed and at the heaviest weight she'd ever been in her life.

When the show premiered eight months later, in June, Simpson had transformed her health, undergoing liposuction and losing over 30 pounds.

The backlash, according to Simpson, was immediate.

"People thought that I just miraculously lost all this weight, like within like a week ... or a month, because they see me on TV, and then they would see a photo that I posted," Simpson told "Good Morning America." "They're like, 'Oh, well, she must be on Ozempic and she lost all this weight doing that.'"

When Simpson, a mom of three, began to share more videos on social media showing herself working out in the gym, the comments questioning how she reshaped her body were plentiful.

"Ozempic much?" wrote one commenter, with another adding, "What's it like to be on Ozempic?"

The pointed comments were referring to a drug used for weight loss. The medications -- Ozempic, Mounjaro, Wegovy and the like -- surged in popularity late last year. Searches for Ozempic alone spiked 450% from 486,000 in June 2022 to 2.7 million in June 2023.

On social media, everyday people shared weight loss success thanks to the drugs, and others questioned which celebrities were privately using them. The social media coverage echoed headlines seemingly keeping a running clock on how celebrities, mostly women, seemed to be losing weight.

"'RHOC' star Emily Simpson accused of using Ozempic after dramatic weight loss," read one headline about Simpson in June.

Simpson said she was not shocked about the conversation around her weight, given that she was also criticized on social media when she was at a heavier weight, a phenomenon that Simpson boils down to "damned if you do, damned if you don't."

What Simpson said took her by surprise was the shaming she received for using Ozempic, which she said she took by prescription for around six weeks in November, losing between five and 10 pounds.

She underwent liposuction on her arms and a breast lift and reduction in January, and since then has focused on exercise and diet alone to lose a total of over 30 pounds.

"People are harder about Ozempic than the liposuction," Simpson said. "People get really angry. I don't understand the anger. That's the part that confuses me."

Why are we still shaming women around weight?

While the body positivity movement -- focusing on the acceptance of bodies of all sizes -- has become more and more mainstream over the years, example after example of people being shamed for taking drugs for weight loss has seemed to stunt that progress.

The headlines and online chatter focused not only on people's sizes and bodies, as they have for decades, but also gave the notion that if female celebrities had taken a medication to reach that body weight, their work was invalidated.

"Kim & Khloé Kardashian Accused Of Using Weight Loss Drugs By Fans," reads one headline from earlier this year.

"Real Housewives Who Have Been Accused Of Using Ozempic," reads another.

Simpson said she felt "forced" into talking publicly about her weight loss after a photo with two of her children she posted on social media sparked headlines about Ozempic.

"I've done so many things in life and I've accomplished so many things, but the one thing that everybody wants to talk about is my size," said Simpson, an attorney by trade. "And it's just exhausting to me."

Ashley Rowe, a 36-year-old mom of three from California, said she debated for three months about whether to start Ozempic.

During that time, she said she saw people in the public eye deny that they were taking a weight loss drug in a way that implied there was something wrong with it.

"It's almost like people can't lose weight anymore without being accused of 'Hey, are you on Ozempic?'" Rowe said. "I ... stopped caring what other people thought and decided I'm going to do what's best for me, but it's sad to see all the shame behind it."

Since starting on Ozempic earlier this year, Rowe said she has lost over 40 pounds.

Who decides the 'right' way to lose weight

Some of the backlash against drugs like Ozempic being used for weight loss stems from the idea that people using the drugs for weight loss are taking them away from people with diabetes, for whom the drugs were designed. Another swath of the anger seems to stem from the fact that the cost of the drugs -- over $1,000 per month without health insurance in most cases -- makes them inaccessible to most people.

Both Ozempic and Mounjaro are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat Type 2 diabetes, but some doctors prescribe the medication "off-label" for weight loss, as is permissible by the FDA. Wegovy is FDA-approved for weight loss.

Some of the biggest shaming around the idea of using drugs for weight loss, however, comes from those who say certain people may not be "obese enough" to be using the medications, and from those who call using drugs for weight loss the "easy way out," despite medical evidence showing otherwise, according to Dr. Caroline Apovian, an endocrinologist and co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

Apovian said the way people are called out for using Ozempic implies that they haven't "earned" their way to being thin, which society still deems as the acceptable size. She said she sees patients who cannot lose weight on their own but still waver on using a medication to help because of the implication that it's somehow "the easy way out."

"With obesity, we think that all you have to do is stop being a glutton and stop being lazy, and it's your moral failure, and you can do something about it, so it's very easy to look at that person and stigmatize them," Apovian told "GMA." "Can you imagine if you said that about somebody who had high blood pressure? 'Oh, she's on Lisinopril [a blood pressure medication], the easy way out. Why doesn't she stop eating salt?'"

Obesity is a medical condition that affects nearly 42% of people in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Obesity-related conditions including heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer are the top causes of premature and preventable death, according to the CDC.

All the ways Ozempic and other drugs like it work in the body show that, as Apovian said, weight is not a matter of willpower or calories alone, and that's the case whether a person has 20 or 120 pounds to lose.

Ozempic and similar drugs mimic the effects of GLP-1, a type of hormone in the body that impacts everything from the brain to muscle to the pancreas, stomach and liver.

Without taking something to change the hormonal levels in the body, people with certain genetics simply cannot lose weight and keep it off, according to Apovian.

"When we try to lose weight with diet and exercise alone, the hunger hormones skyrocket and the satiety hormones drop, and it is almost impossible to keep the weight off," she said, adding, "There are powerful hormonal forces that are pushing the body to gain the weight back."

Doctors say shaming can be more dangerous than the drugs

Dr. Terry Dubrow, a board-certified plastic surgeon and star of the TV show "Botched," said cultural shaming around using prescribed medication to help with weight loss can have "dangerous" medical ramifications.

For example, a person not admitting they are on a drug for weight loss to their doctor or a loved one can have medical complications.

"My colleagues in my hospital are telling me they're seeing tons of patients having elective surgery who lied about being on these drugs," Dubrow said. "So, instead of having empty stomachs, they're now basically putting people under anesthesia who have fuller-type stomachs and they're seeing a lot of aspiration."

Last month, the American Society of Anesthesiologists issued new guidance for when patients should stop taking GLP-1 receptor agonists before surgery. The new guidance was issued after "many reports from medical literature and anesthesia leaders about people who fasted but still vomited either going to sleep or waking up from anesthesia," said Dr. Ronald L. Harter, M.D., fellow and incoming president of the ASA and professor of anesthesiology at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Dubrow said he believes that as more and more people understand what the medical research now shows -- that obesity is a medical disorder, not a result of lifestyle choices -- the shame around Ozempic and other weight loss drugs, which he describes as the "cure for obesity," will fade away.

"It's a disease like diabetes. It's a disease like heart disease," Dubrow said, adding, "So, treat obesity as a disease. Stop treating it as something to be embarrassed about."

Apovian agreed, noting that she sees hope, but adding that it can take a long time to make societal and medical shifts in how we think about obesity.

"It takes a while to change the paradigm, to change the opinion and the understanding," Apovian said. "There are doctors out there who believe that it's diet and exercise ... so, you can imagine the lay person out there, the government, the communities. Everybody is struggling to understand this new dogma."

Shaming aside, Ozempic changed their lives, they say

For Rowe, who struggled for years to lose weight after giving birth and being diagnosed with endometriosis, she said Ozempic has changed her life. In addition to taking the weekly injection, Rowe said she has changed the way she eats and is working with a behavioral therapist.

"It is so much more than just taking an injection," Rowe said. "I feel like sometimes people think they can start this shot and do their same habits."

Simpson said when she took Ozempic, she noticed changes in her cravings and eating habits, changes that she said she was able to carry on even after stopping the medication. She said she did so at the time in order to prepare for surgery.

"For me, it was just those three things all coming together that got me to this point," Simpson said, referring to the combination of Ozempic, liposuction, and diet and exercise. "I feel the fittest I have in eight years. I feel the happiest I have in eight years. I feel like I have more energy than I've had in years, and I'm very happy and very content where I am."

In an ideal world, Simpson said, how a woman takes care of her own body would not be something left to public consumption and judgment.

"I just don't understand why we feel the need to shame someone because they did something differently than someone else would," she said. "It doesn't make sense to me because, ultimately, we all just want to be our healthiest and our fittest for ourselves and our families."