James Harden vs. Luguentz Dort is the NBA's best one-on-one battle

The best one-on-one battle going, and certainly the one with the biggest name recognition gap, resumes Wednesday night in a pivotal Game 5 between the Oklahoma City Thunder and Houston Rockets: James Harden against Luguentz Dort.

So far, these have been the playoffs of the isolation -- and specifically the one-on-one drive. In the regular season, only one team -- the Rockets -- averaged more than 20 isolations per 100 possessions, according to Second Spectrum. (They checked in at 37, almost double anyone else. Harden, perhaps the greatest one-on-one player ever, averaged 26 by himself -- more than any other team.)

Through nine days of playoff action, six teams are averaging at least 22.8 isolations per 100 possessions. Both the Thunder and Rockets have eked past Houston's regular-season number. The Indiana Pacers sniffed it against the Miami Heat.

Postseason basketball has always shifted toward mismatch-hunting and one-on-one play. The best defenses take away most of your pretty motion-based stuff, leaving predatory grunt work.

But the jump in isolations from the regular season to the playoffs is more pronounced, and replicating across more teams, than a year ago -- both for the full postseason and the first round alone. Teams are searching more for mismatches they can drive, not mismatches they can post up. The game has been tilting that way for years for lots of reasons -- rule changes, player skill sets, math -- but the first round (a small sample!) seems to have brought an acceleration of that trend.

Some of this is the product of specific matchups. Without Domantas Sabonis, the Pacers were reduced to going one-on-one against whomever they deemed Miami's most vulnerable perimeter defender. The Utah Jazz are merciless abusing Denver's weakest links. (Michael Porter Jr. and Nikola Jokic have tire tread on their jerseys, though Porter played maybe the best defensive quarter-plus of his life when the Nuggets needed it while facing elimination Tuesday.) Jamal Murray got into the act in Game 5 with drives against Joe Ingles and a Murray flurry (hat tip: Chris Marlowe) of step-backs to ice it. Even Denver's isolation volume is way up.

The one-on-one gambit appears to be working to a relative degree, though it's early. Only four teams cracked one point per possession on isolations in the regular season, per Second Spectrum. Seven are busting it in the playoffs so far, with the Milwaukee Bucks, Pacers, and Jazz all at about 1.15 points per isolation. (Utah was incinerating Denver to the tune of 1.25 points per iso before running into stiffer resistance in Game 5.)

A lot of Houston games evolve (devolve?) into isolation-fests. The Rockets live in that world. Their switch-almost-everything scheme drags opponents into it. Pick-and-rolls against Houston don't open the same creases -- or trigger the same rotations -- as against everyone else. That leaves one-on-one play. It happens the Thunder averaged 19 isolations per 100 possessions -- second in the league.

Oklahoma City's three point guards -- Chris Paul, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, and Dennis Schroder -- are accomplished one-on-one players with very different methods. Paul is the patient midrange assassin. Gilgeous-Alexander confuses defenders with an arrhythmic start-and-stop game; different parts of his body appear to be going in different directions, at different speeds, at the same time. Schroder is hunched-over lightning. The stylistic variety is appreciated.

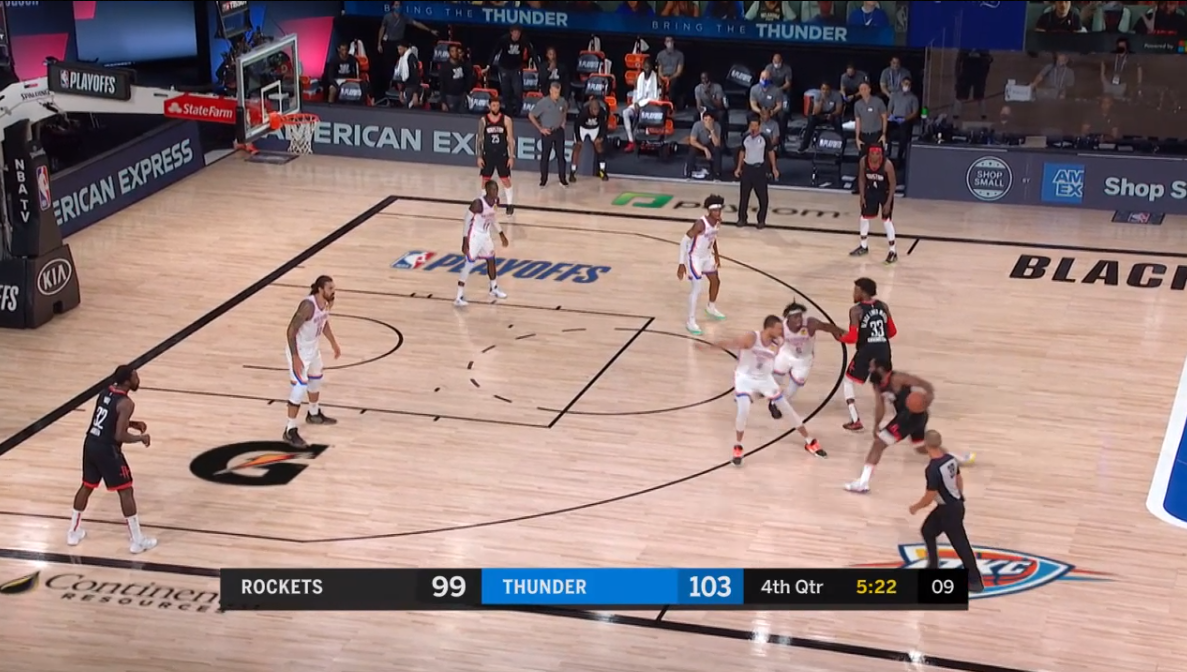

Harden, of course, has every gear and cadence. He has met a worthy adversary in Dort -- a human cinder block with quick feet and an unrelenting motor who played most of the season on a two-way contract. The Thunder are 2-1 in this series with Dort available, and he has taken the Harden assignment almost every second he has logged. There are maybe four or five humans alive -- if that -- who can do this to James freaking Harden:

The Rockets in Games 2-4 have averaged 0.934 points per possession when Harden shoots out of an isolation, or passes to a teammate who fires -- down from a monstrous 1.15 in the regular season, per Second Spectrum.

You can tell Harden is not exactly enjoying the Dort experience. Houston set 56 ball screens for Harden in Game 4 -- the second-highest total (by one measly pick) of any Rockets game this season, and by far the highest since they stopped playing centers, per Second Spectrum. The total from Game 3 -- 38 ball screens -- is in their season top 20, and No. 3 among games A.C. (After Centers). The Rockets want to dislodge Dort from Harden. (Dislodging Dort sounds like a medical procedure that requires an overnight hospital stay.)

They sometimes try catching Dort off guard with back picks at half court, a tactic Houston busts out to help Harden escape an inconvenient matchup and provide him a long runway:

Dort is not cooperating. The Thunder do not want to switch against Harden. He can blow by Oklahoma City's bigger players and plow through their point guards. They don't care that refusing to switch leaves some of Houston's shooters -- including Harden's screen-setters -- open for a moment. (There may be some opportunism in Houston setting all those picks.) If Jeff Green and Robert Covington and P.J. Tucker beat you with semi-contested above-the-break 3s -- as opposed to corner 3s -- you tip your cap and go home:

Behold Dort navigating three Covington screens in five seconds -- under, over, under:

Dort has risked the occasional duck-under strategy. It's an interesting gamble you can probably spring on Harden a few times per game. Harden is too good a shooter for it in the aggregate, but he's not Stephen Curry or Damian Lillard. It's also a bet on Harden's finicky nature: He loves prodding for something just a little better. But Harden has burned Dort for going under a couple of times.

The other four Oklahoma City defenders have responded in kind to whatever Dort does.Danilo Gallinari's flash into Harden's line of sight on the above play buys Dort time to recover:

Dort falls behind this Danuel House Jr. screen, but Gilgeous-Alexander and Darius Bazley cover for him -- and for each other:

Gilgeous-Alexander lunges out to deter Harden from driving; Bazley zones up between Gilgeous-Alexander's man (House) and Green until the defense resets:

Harden resorts to something of a post-up, and he has been doing more of that against Dort, too. Harden recorded four post touches in both Games 3 and 4, tied for his season high -- and a number he reached in only four games this season, per Second Spectrum. From afar, those post-ups feel like Harden digging deeper for alternatives.

Dort has proven so valuable as to chip away at the minutes for Oklahoma City's best lineup -- and the best in the league in terms of per-possession scoring margin: Paul, Gilgeous-Alexander, Schroder, Gallinari, and Steven Adams. That fivesome has logged 19 minutes in the past three games -- a decent chunk for a non-starting group, but perhaps not as much as you'd expect in a nip-and-tuck series. The Thunder are rushing that group -- or variants featuring all three point guards -- onto the floor whenever Harden rests, and Dort becomes less essential.

It took almost three full games, but Billy Donovan finally unveiled a smaller lineup I speculated he might use on the Lowe Post podcast previewing the series: the three point guards, Dort, and Gallinari as small-ball center. That group is plus-16 in 11 minutes. Donovan should use it more, even at Adams' (slight) expense.

For Adams to be an asset against Houston, he has to devour offensive rebounds and score in the post. He has gotten better at the latter, but it's not his natural inclination. It's also hard to play Dort and Adams (or Nerlens Noel) -- two total non-shooters -- together. The Rockets ignore Dort and plant his defender in the paint to clog Oklahoma City's driving game. (The series will come down to lots of small things, including whether Dort cans a few more wide-open moonball 3s than expected.)

The Thunder have tried to mitigate Dort's clanky shooting by sliding him into some off-ball screening action:

Gallinari slips pretty hard out of that pick. That's a classic anti-switch tactic: Abort the screen before the defense completes its switch. Adams does that on a lot of ball screens. Paul is trying to fool the Rockets a few times per game with fake handoffs. Houston has generally read all that stuff -- and sensed when it is better to stay home than switch. Part of being a great switching defense is knowing when not to switch.

Screening trickery with Dort can do only so much damage control. The efficiency of Oklahoma City's isolation scorers -- of all isolation scorers -- is tied to the level of shooting around them. The more bodies defenses can position between a scorer and the basket, the harder it becomes for that scorer to beat you. This is the main reason Houston traded Clint Capela -- to get him and his defender out of Harden's (and Russell Westbrook's) way.

Playing three non-shooters -- Dort, Noel, and Bazley -- is a recipe for droughts, even if Bazley's accuracy is catching up to his confidence. (He's 6-of-10 from deep in the playoffs.) Donovan excised Hamidou Diallo midway through Game 2 because Oklahoma City couldn't score with him on the floor. He tried Abdel Nader, and if the Thunder have to steal minutes on the wing, Nader is probably the better call. Mike Muscala got a look at backup center; he can shoot, but the Thunder risk hemorrhaging points with him on the floor.

The Paul/Schroder/SGA/Dort/Gallo lineup lands in a nice middle ground. It can play fast, and the Thunder want to score before Houston sets its defense.

OKC can compete with Houston on Houston's terms. The Thunder guards can hurt Houston one-on-one. They hunted Harden down the stretch of Game 3, and he offered zero resistance. Covington has no shot staying in front of Gilgeous-Alexander or Schroder.

(Covington has played only 14 postseason games, but the playoffs have been a little harder on him. Remember: The Sixers benched him in the second round against Boston in 2018. The more one-on-one nature of the playoffs has something to do with it. Covington can't get his own shot and is a better team defender than isolation defender.)

Houston has tons of answers. One is that Harden is amazing. Even amid Dort-mania, he scored 70 points over Games 3 and 4 on good efficiency. He will figure some things out about this mystery man/fire hydrant.

The Rockets might try using Eric Gordon more as Harden's screener; Gordon can make enough pick-and-pop 3s to punish the Thunder. Oklahoma City usually has Gilgeous-Alexander on Gordon, and Harden can attack that matchup if the Thunder start switching. Covington can get on pick-and-pop hot streaks, too.

Having Harden's screeners slash down the gut can unlock profitable looks:

(House is playing really well on both ends.)

The Green-Harden pick-and-roll has been bizarrely effective. (Are we sure that is really Jeff Green, by the way? Did Houston discover some sort of cloning technology?) When the Thunder see that coming, they need to have Green's man get as low as possible to scoot under Harden's screen.

It's always healthy to mix in sets that get Harden in motion -- maybe by flying off a pindown on his way to the ball -- before he goes into attack mode.

Westbrook's return would give Houston more options -- and more juice when Harden rests. But Dort's presence has changed the terms of engagement.